HARDRAW FORCE

England's Highest Single Drop Waterfall

The Great Flood of 1899.

The Dales is a limestone area and the rock is very porous.

As a result rainwater flows quickly into the water course causing

rivers to rise and fall dramatically in a short space of time.

This is why the waterfall is best viewed after heavy rain when

Hardraw Beck is in flood turning into a raging torrent.

Those who visit the area in the summer months when the falls are a mere trickle will scarce believe the ferocity of the angry beck which regularly breaks it banks spilling out into the fields before flowing into the valley below.

The awesome potential of the waters were demonstrated only too dramatically in July 1899. Barry Cockcroft recalls the events of that terrible day in his book 'The Day the Dale Died'.........

"Indeed, 12th July 1899 dawned brightly in Upper Wensleydale and continued fair all morning. But at noon, curiously the same time as the bursting of the Grisedale ‘blister’, (8th August 1899) the sky above Great Shunnor Fell darkened dramatically and the havoc began. It was as though the bottom had fallen out of a giant bucket in the sky, so ferocious was the rain. Hailstones more than an inch long tumbled down, smashing twenty windows in one house alone, and the whole affair was orchestrated by sheet lightening and immense peals of thunder.

Thousands of tons of water roared down the slopes of Shunnor, which rears to a height of 2340 feet, and then divided to attack both Wensleydale and Swaledale.

But the most spectacular blow was reserved for the village of Hardraw, just above Hawes in Wensleydale, which thrived on the visitors who came (and still come) to see the lovely, pencil slim waterfall which tumbles a hundred feet over Hardrow Scar behind the ancient Green Dragon Inn. The amazed villagers saw a wall of water several yards high racing towards them along and around the course of Hardrow Beck and over the Scar. They ran to their bedrooms and waited in terror as it tore apart their graveyard, washing out coffins and carrying gravestones more than two miles down the valley, and floated their furniture up stairs to meet them. A large tree crashed into the wall of the Green Dragon, which sustained the worst damage of any building in Hardrow (a point no doubt exploited by the Methodist preachers in subsequent sermons about the evils of drink) The flood smashed through the rear doors and windows and out again in the same manner at the front, taking the furniture with it and destroying most of the stock in the cellar.

Pausing only to reduce the pretty stone bridge in the center of the village to a tottering ruin, the waters raced on to swamp Hawes and other low-lying areas. Many farmers lost up to forty sheep each, plus hundreds of lesser animals, and walls, fences and meadow lands were laid waste over a large area. And when the people of Hardrow crept downstairs and picked their way through the mud and rubble to inspect the damage the sight which dumbfounded them most of all was Hardraw Scar itself. It had been totally dismantled.

Gone was the elegantly shaped fall, which leapt so prettily into the pool below. The lip of the Scar had been torn away, and after a few days when the fells had finally drained, the water slithered miserably down the mud, slime and debris.

The awesome news spread through the county and the Yorkshire Post dispatched a

reporter and artist to the scene. So overwhelmed was this scribe that he began his report thus:

The awesome news spread through the county and the Yorkshire Post dispatched a

reporter and artist to the scene. So overwhelmed was this scribe that he began his report thus:

‘In attempting anything like a realistic description of the havoc wrought in Wensleydale and Swaledale, and particularly at Hawes and Hardrow Scaur, one cannot but feel oppressed somewhat by the magnitude and difficulty of the undertaking. To really and truly convey to those who know and delight in such a lovely bit of nature as Hardrow Scaur an adequate impression of the desolation which now exists where beauty reigned supreme is a task which calls for a picturesque pen such as conceived the beautiful ending of the Mill on the Floss.’

But our man did not do at all badly when he finally got down to it.

‘ The stretch of soft turf that used to form the approach to the Scaur is now a swamp, in which are embedded trunks of trees, naked of their green livery, and huge boulders washed down from far up the valley. All that is left of the old doorway through which visitors were admitted is the solid masonry upon which it hung. The rest has been cut off as cleanly as with a knife, and of the wall that adjoined-unmortared, it is true, but six feet high and nearly four feet thick-only the merest fragment remains.

‘All the bridges have disappeared as completely as if they never existed; here and there a few stones mark the site of what were before the flood the romantic paths that constituted part of the charm of the Scaur, but they are very few. Turning the corner we come in sight of the fall-the highest in England. It is still there, it is true; the water still falls over the height and into the pool below with a sonorous roar, but all the surroundings have changed. The grassy slopes which rose on either side of the pool are no more.'

Those who visit the area in the summer months when the falls are a mere trickle will scarce believe the ferocity of the angry beck which regularly breaks it banks spilling out into the fields before flowing into the valley below.

The awesome potential of the waters were demonstrated only too dramatically in July 1899. Barry Cockcroft recalls the events of that terrible day in his book 'The Day the Dale Died'.........

"Indeed, 12th July 1899 dawned brightly in Upper Wensleydale and continued fair all morning. But at noon, curiously the same time as the bursting of the Grisedale ‘blister’, (8th August 1899) the sky above Great Shunnor Fell darkened dramatically and the havoc began. It was as though the bottom had fallen out of a giant bucket in the sky, so ferocious was the rain. Hailstones more than an inch long tumbled down, smashing twenty windows in one house alone, and the whole affair was orchestrated by sheet lightening and immense peals of thunder.

Thousands of tons of water roared down the slopes of Shunnor, which rears to a height of 2340 feet, and then divided to attack both Wensleydale and Swaledale.

But the most spectacular blow was reserved for the village of Hardraw, just above Hawes in Wensleydale, which thrived on the visitors who came (and still come) to see the lovely, pencil slim waterfall which tumbles a hundred feet over Hardrow Scar behind the ancient Green Dragon Inn. The amazed villagers saw a wall of water several yards high racing towards them along and around the course of Hardrow Beck and over the Scar. They ran to their bedrooms and waited in terror as it tore apart their graveyard, washing out coffins and carrying gravestones more than two miles down the valley, and floated their furniture up stairs to meet them. A large tree crashed into the wall of the Green Dragon, which sustained the worst damage of any building in Hardrow (a point no doubt exploited by the Methodist preachers in subsequent sermons about the evils of drink) The flood smashed through the rear doors and windows and out again in the same manner at the front, taking the furniture with it and destroying most of the stock in the cellar.

Pausing only to reduce the pretty stone bridge in the center of the village to a tottering ruin, the waters raced on to swamp Hawes and other low-lying areas. Many farmers lost up to forty sheep each, plus hundreds of lesser animals, and walls, fences and meadow lands were laid waste over a large area. And when the people of Hardrow crept downstairs and picked their way through the mud and rubble to inspect the damage the sight which dumbfounded them most of all was Hardraw Scar itself. It had been totally dismantled.

Gone was the elegantly shaped fall, which leapt so prettily into the pool below. The lip of the Scar had been torn away, and after a few days when the fells had finally drained, the water slithered miserably down the mud, slime and debris.

‘In attempting anything like a realistic description of the havoc wrought in Wensleydale and Swaledale, and particularly at Hawes and Hardrow Scaur, one cannot but feel oppressed somewhat by the magnitude and difficulty of the undertaking. To really and truly convey to those who know and delight in such a lovely bit of nature as Hardrow Scaur an adequate impression of the desolation which now exists where beauty reigned supreme is a task which calls for a picturesque pen such as conceived the beautiful ending of the Mill on the Floss.’

But our man did not do at all badly when he finally got down to it.

‘ The stretch of soft turf that used to form the approach to the Scaur is now a swamp, in which are embedded trunks of trees, naked of their green livery, and huge boulders washed down from far up the valley. All that is left of the old doorway through which visitors were admitted is the solid masonry upon which it hung. The rest has been cut off as cleanly as with a knife, and of the wall that adjoined-unmortared, it is true, but six feet high and nearly four feet thick-only the merest fragment remains.

‘All the bridges have disappeared as completely as if they never existed; here and there a few stones mark the site of what were before the flood the romantic paths that constituted part of the charm of the Scaur, but they are very few. Turning the corner we come in sight of the fall-the highest in England. It is still there, it is true; the water still falls over the height and into the pool below with a sonorous roar, but all the surroundings have changed. The grassy slopes which rose on either side of the pool are no more.'

The Flood cont'd...

The one on the right hand has vanished; the other is a shrunken, denuded mound of mud and bedraggled grass.

They happened to stand in the way of the torrent as it came down in full cry, and were swept away as it impetuously cut for itself a new path. On top of the fall there are significant signs of the force with which the water rushed over the cliff. As below, fallen trees lie everywhere, the masonry has been carried away bodily, while the ironwork lies a hundred feet below. As if to leave proof of her strength, Nature has suffered one iron bar to remain in its socket, but bent like a rod of tallow, and its end frayed and torn like a wisp of hay.

‘On the right side there still stands an iron gate, fastened with one of the latest modern patent locks, the design being, no doubt, to secure the privacy of this particular walk. The water has cut away every vestige of the walls on either side, yet it has left the iron gate and its patent lock standing to indicate where once the pathway led! In her wayward moods Nature is as capricious and as whimsical as a light-o-love.

Still standing amongst a number of uprooted companions is one big tree, but, using as a knife a huge paving stone with a sharp edge, the water has stripped the tree of its bark as deftly as ever savage did to fashion his bark canoe. By dint of so much climbing, by crossing the river half a dozen times, and (incidentally) falling in once, we reach the point at which the Scaur opens into the valley above. Of the cart road that crossed the beck at this point no trace remains.

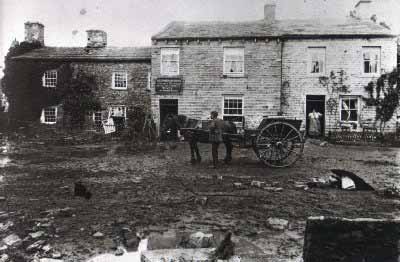

There is a sort of plateau here, and the water, spreading out, treated moor, meadows full ready for the scythe, and roadway with strict impartiality, and equally boisterous roughness. In the leisurely fashion common to roadside labourers a gang of men were seeking to restore a semblance of roadway by staking with the few remnants left of the walls that originally stood on either side. 'A little higher up, in the midst of a sea of mud and water, stands a little farmstead, and the farmer is ready enough to talk. He was to have cut his hay crop on Thursday, he says: they were beautiful meadows, too, but now they are buried under a foot of clay and mud. Where will he begin the work of reclamation? Where, indeed, he echoes. t'is a summer’s work; he and his son cannot attempt it, and so he stands and watched his ruined meadows.'

Another visitor came to stare aghast at the shattered Scar and he proved to be a man who had the power to fight back against Nature. He was Lord Wharncliffe, and he happened to own not just the Scar but all the land around it. He turned to his estate manager and commanded: ‘Put it all back’

No doubt identifying keenly with the emotions of Hercules upon being given the Augean stables task, the manager set about his work. He must have hired not just the very best masons in Wensleydale, but very sure-footed ones. They inched out along the top of the Scar, reconstructing and building back the lip, cunningly pinning together blocks of stone to make it look natural.

It was a stunning job they did. When they had finished the fall was as spectacular as before. Very few of the thousands of people who today pay their fee at the Green Dragon to view Hardrow Scar realize that it runs over a man-made top.

Another account of the flood is given by John William Sharples in the book on Wensleydale by Ella Pontefract and Marie Hartley published in 1936. Mr Sharples born in the village and was 70 years old at the time of writing living in the cottage next to the Green Dragon. Is memory of the flood is therefore from first hand experience.

‘’I must tell you that time there was a cloudburst over Shunner Fell,’’ he said. ‘’I was only a young man at the time and was working at a quarry in Garsdale, but I’d lamed myself and was off work. I was living at Scar End at the time, so I’d a wonderful chance of seeing the storm.

‘’I’ve never seen as much water come down as that particular day, and the Green Dragon was flooded out. There was water nearly halfway up t’walls in the lower rooms and half a foot o’ mud on t’floors. There was a horse standing belly deep in a stable opposite t’Inn, and some pigs next door swam out o’ t’building over bottom half o’ t’door. They escaped down the fields.

‘’It was July, and the storm came after dinner. There was thunderin’ and lightnin’ every minute and hail stones as big as marbles. Fish were swept from t’ river on to t’banks, and t’low side of Hardraw meadows were covered with mud. Hardraw Bridge was swept away, and iron railings were bent by t’force o’ t’water.’’

Writing in the book 'About Hardraw'..........

From the first contest in 1880 the events were well-supported by the whole of the North of England until, on Wednesday, the 12th July, 1899, a tremendous thunderstorm, or cloudburst, ruined the old Scaur and made a new watercourse. The adventures of Hardraw village in that flood disaster make a separate epic, but in the Green Dragon Inn, through which access to the Scaur is gained, they still show the mark in the tap- room and on the inside door to which the flood-waters reached.